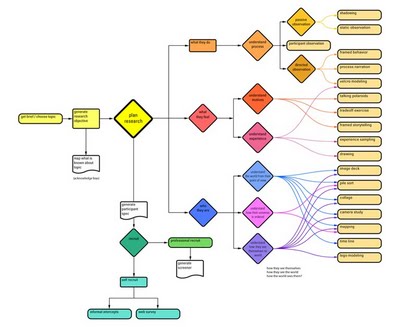

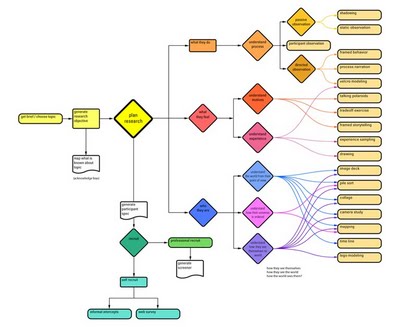

By way of an explanation for why I haven't posted lately, this last term was consumed by two projects: finishing the plan for what I've come to call the "tool picker" (above) to help designers new to qualitative research expand their palette of methods, plus a set of analytical tools to use on the research data.

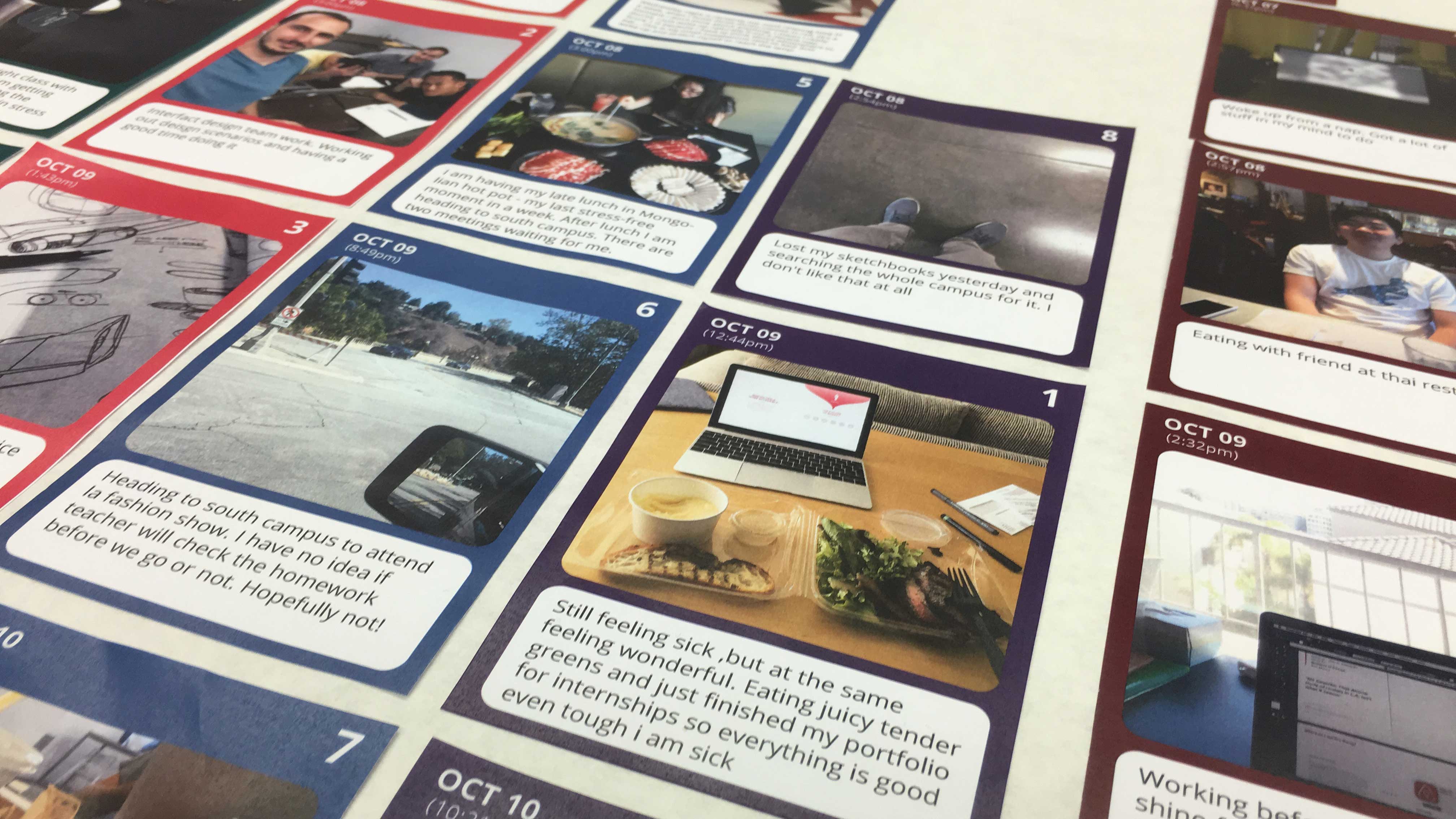

This, on top of a term of research for a multi-term project for the American Red Cross, kept me busier than a dot painter in a paisley tie factory. I'll post more on all of this in the upcoming weeks.

The so-called "tool picker," above, is an attempt to help designers explore beyond a set research methodology. As currently taught (and sometimes practiced), design research is often treated as a constant set of tools and, as a result, students tend to think that it's a standard process. The field of design research has evolved into a complex landscape of approaches, however, and good design practice stays abreast of these developments.

In order to help my students break out of a narrow approach and yet negotiate the complexity of the myriad methods in practice today, I am attempting to acquaint them with a comprehensive and yet manageable set of methods. Also, I need to equip them with an understanding of why, and in which situations, a particular approach would be effective.

Currently, the research approach is chosen by those with expertise. There is a "guru" who brings years of experience to bear on the decision. Is there a way to enable beginners to more quickly gain the experience necessary to know which approach might be best for a given problem?

I distilled the complex set of approaches in use today into a set of eighteen (you see them down the right-hand side of the diagram, above). I will be creating a decision-making tool to guide the students through the decision process by asking a series of questions about what type of knowledge they seek for a given topic.

Starting at the left-hand side with a careful choice of topic, students are asked to generate a research objective statement. We discuss issues of ethics, scope, appropriateness, and so forth, and gain explicit knowledge of the researcher's bias.

Moving on to the decision process (while at the same time generating specifications of which sorts of participants will be recruited and engaging in the recruitment process), students begin to consider the type of knowledge they seek. We consider three general areas of knowledge about the user: what they do, what they feel, and who they are. Moving right-ward through the diagram, you can see how we move into finer levels of discrimination, arriving at a recommended set of methods.

This is a first rough design for the tool. When I first completed this version, I was disheartened at first by seeing that, if one worked backwards through the chart one could see that a skilled researcher could use any of the tools to uncover any of the types of knowledge desired. But I reminded myself that this is a decision tree that helps beginners and widens their view beyond a limited single-thread process. The tool is designed to lead them to the most appropriate choice, by no means the only choice possible. Once they've used the tool for a few projects, they will begin to gain knowledge of the wider set of approaches and begin to see how the different methods work in different cases. Once they begin to see that the tools actually can be tailored to many purposes, they are right where I want them: imbued with a robust working knowledge of the multivariate research process.

Monday, October 19, 2015 at 2:18PM

Monday, October 19, 2015 at 2:18PM

Katherine Bennett | Comments Off |

Katherine Bennett | Comments Off |