What I'm Up To

Wednesday, December 31, 2008 at 11:15AM

Wednesday, December 31, 2008 at 11:15AM My goal is to be able to teach product design students how to do credible and effective qualitative design research. Most product designers are at first focused on the methods, like we would be on any set of tools. Give me the tools, and I'll use 'em. I think this comes from how we learn the design process. It is a standard sequence—investigation, problem definition, ideation, concept generation, concept refinement, final design specification. We learn it by doing it, over and over. We expect that any problem can be solved by the application of this process, and for the most part this is true.

The investigation stage, however, has its own set of tools (methods), borrowed from science, psychology, anthropology, etc., and there is no standard set that applies to all situations. It is important to know not only the methods that are out there, but also the rationale behind their application. And nobody has a complete list. For example, Brenda Laurel’s Design Research cites 36; the Design and Emotion Society’s Methods and Tools web site describes 57 (not all research—some of those are analysis); and IDEO outlines 36 research and 15 analysis tools in their Method Cards. After reviewing these and other sources and allowing for duplication, I have found 52 distinct techniques for research and 18 for analysis (and I've only begun to compile a list of those).

Many design firms' initial experience with research is via the hiring of a specialist. They observe the process that that person uses for a particular investigation and assume that that is "the process," (it's as if they think that, like design itself, design research has a universal process applicable to all situations). Some offices then polish up that process, giving it a catchy name and graphic veneer, and add it to the list of their firm's capabilities as a branded form of research, much like they began to offer engineering capability in the 80s. It's a way of making their firms more marketable. In the competitive environment of today's consulting offices, this is understandable and necessary.

The problem is that the research approach should differ depending on the issues under investigation. Good research takes into consideration the entire palette of methods available and chooses the right set to uncover the necessary knowledge in each situation. It's vitally important, then, to understand the rationale behind each choice.

And above all it is important that designers understand that qualitative research is not merely a kit of tools, it is an approach. At its heart is an immutable demand: to understand and have empathy with the point of view of all customers and stakeholders in a situation. In order to gain this understanding one must make smart decisions about which methodologies to employ. [I use the term methodology to mean the tool, or method, plus the rationale behind using it.]

So my goal is twofold: first, to acquaint my students with at least a basic set of methods, and second, to enable them to understand why, and in which situations, a particular one would be effective.

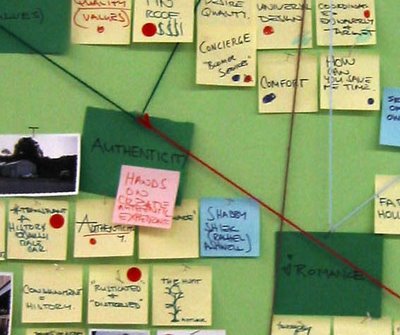

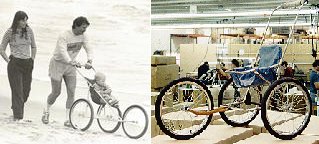

I continue to teach my course the way I've done it since 1991: using the time-honored project-based learning we're accustomed to—learning by doing. The students engage in fourteen weeks of field research and analysis (in some cases, more than one term's worth, as in Laura Dye and Heather Emerson's Camp Boomer project, above), culminating in a research presentation. They choose the topic and I advise them on approaches that would be effective. The problem with this is that the students, like the consulting firms I describe earlier, often come away from the experience thinking that there is one way to do research.

To remedy this I have added a theoretical component that teaches the wider range of methods and their accompanying rationales. A survey of the methods is followed by learning the principles behind their application via the case study method. The cases are written specifically to teach design research, and each case centers on important axioms. Much like the case study method pioneered by the Harvard Business School, the cases provide opportunities for students to engage in discussions centered on the decision process involved. Instead of discussions about management theory, the cases I am writing focus on the decisions necessary for planning research activities. A range of cases allow students to act out the planning process—and choose approaches—for research that would apply to a variety of design problems.

So far, I've got that long list of methods and am working on descriptions of each of them (broken down into: a brief description, an example, the objective, the procedure, the rationale, advantages and limitations, and citations of references where one could go for more examples, papers by those who have used the approach, etc).

I've got a few simple cases that I have used to teach basic axioms, and am working on some larger ones with research specialists from a couple of well-known firms. Both are excited about my doing this work, and although it's a tall order to flesh these out, it will be worth it.

While I started out like many product designers, focusing on finding "the right kit of tools," I have come to realize that the so-called tools are only a means to an end. What really matters is how smart you are at analyzing what you get from using them, and figuring out what it means.

Katherine Bennett | Comments Off |

Katherine Bennett | Comments Off |  Art Center,

Art Center,  IDEO,

IDEO,  case study method,

case study method,  design research,

design research,  pedagogy

pedagogy